Why Tension Often Accumulates Quietly Over Winter

Introduction

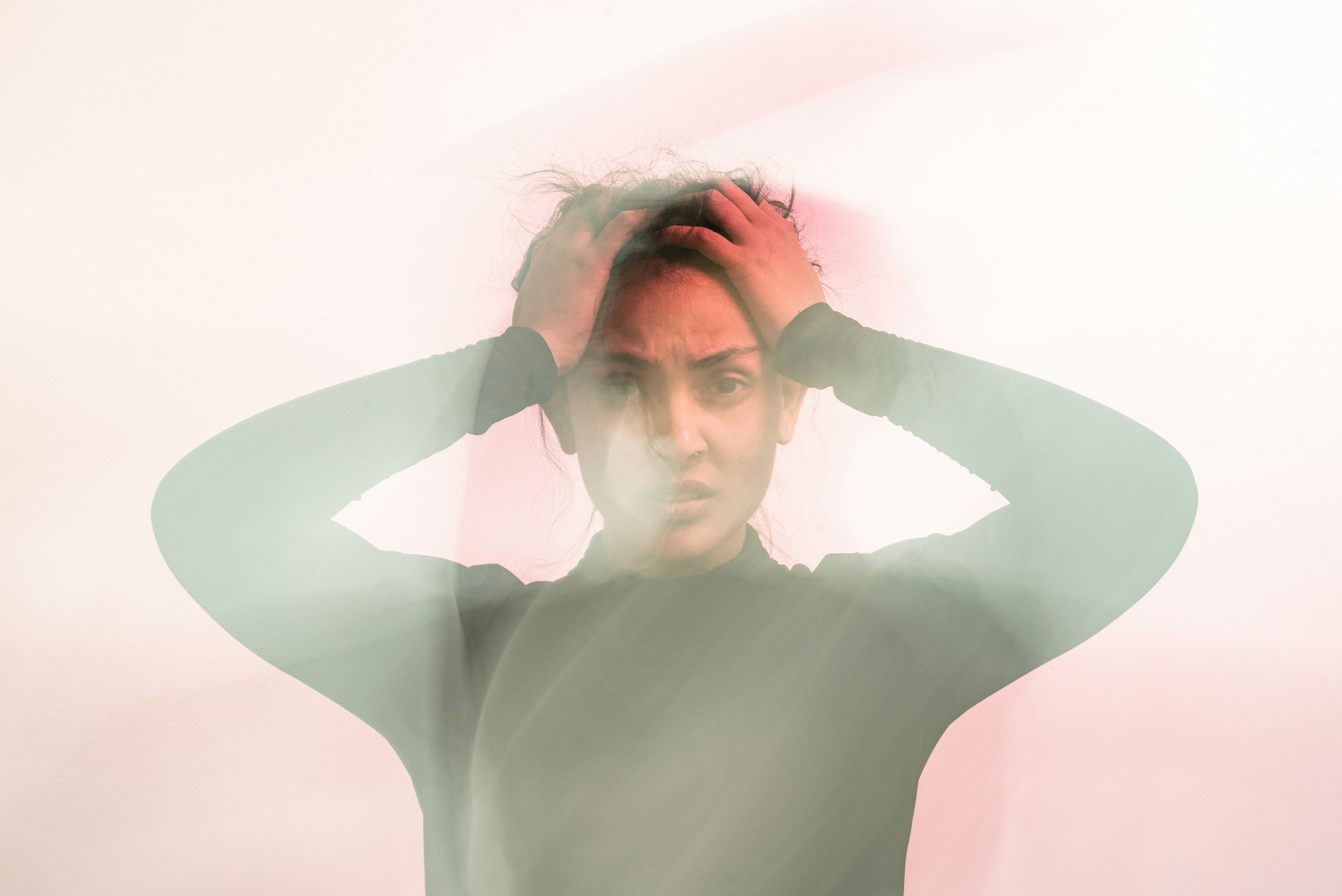

Many people reach the end of winter feeling unexpectedly tight, tired, or heavy in their bodies, even if nothing specific feels “wrong.” There may be no clear injury, no single stressful event, and no obvious explanation. And yet, stiffness has crept in. Sleep feels less restorative. Muscles feel guarded. Energy feels muted.

This accumulation of tension is rarely sudden. It builds quietly over the winter months, shaped by changes in light, movement, temperature, routine, and nervous system demand. Because it happens gradually, it often goes unnoticed until the body begins to ask for attention more clearly.

Understanding why winter creates this slow buildup of tension helps explain not only how the body responds to seasonal change, but why gentler, more supportive approaches are often needed as winter comes to an end.

The Body Responds to Winter Before the Mind Does

Seasonal change is not just psychological. It is deeply physiological. As daylight decreases and temperatures drop, the body subtly shifts into a more protective state. Movement patterns change. Muscles brace more easily. Breathing becomes shallower. Circulation slows.

According to Harvard Health Publishing, colder temperatures can lead muscles to contract and stiffen more easily, especially when combined with reduced physical activity. Over time, this low-grade muscular contraction becomes habitual rather than situational, meaning the body holds tension even when it is no longer necessary.

The nervous system adapts to winter by prioritizing conservation and protection. While this adaptation is useful in the short term, extended periods in this state can lead to chronic tension without obvious warning signs.

Reduced Movement Creates Hidden Holding Patterns

Winter often brings a natural reduction in movement. Shorter days, colder weather, and indoor routines mean fewer walks, less spontaneous motion, and longer periods of sitting.

The Cleveland Clinic explains that prolonged inactivity allows muscles and connective tissue to shorten and stiffen, particularly in the hips, lower back, neck, and shoulders. Unlike acute muscle tension, this kind of stiffness does not announce itself loudly. It settles in gradually and becomes the body’s new baseline.

Because these changes happen slowly, the body adapts around them. Posture shifts. Range of motion decreases slightly. Compensation patterns form. By the time discomfort is noticed, tension has often been present for weeks or months.

The Role of the Nervous System in Winter Tension

Tension is not purely mechanical. It is also neurological.

During winter, the nervous system receives fewer cues of safety and regulation. Less sunlight affects circadian rhythm and mood. Disrupted sleep patterns increase stress sensitivity. Social rhythms often become more condensed or emotionally demanding around the holidays.

The American Psychological Association has noted that chronic low-level stress can keep the body in a state of heightened muscular readiness, even in the absence of immediate threat. Muscles remain partially engaged as a protective reflex, particularly in the neck, jaw, shoulders, and lower back.

When stress is ongoing but not dramatic, the body rarely releases this tension on its own. Instead, it becomes stored.

Why Tension Builds Without Pain

One of the reasons winter tension goes unnoticed is that it does not always present as pain. More often, it shows up as subtle limitation.

Movements feel less fluid. Turning the head feels slightly restricted. The body feels heavier rising from rest. Fatigue appears sooner than expected.

According to research published in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, chronic muscle tension often develops beneath conscious awareness and is perceived as normal until movement or touch brings attention back to the area. In other words, the absence of pain does not mean the absence of holding.

The body adapts to tension by reorganizing around it, which allows function to continue but increases long-term strain.

Cold Weather and Protective Bracing

Cold temperatures trigger an instinctive response to protect vital organs. Muscles contract to preserve heat. Posture becomes more guarded. Shoulders rise. The chest subtly closes.

Harvard Medical School notes that cold exposure can increase muscle tone and joint stiffness, particularly when circulation is reduced. Over time, this protective bracing becomes habitual, even indoors or in warmer environments.

Because this response is unconscious, it rarely resolves without intentional intervention.

Emotional Accumulation Mirrors Physical Holding

Winter is also a time when emotional processing slows. Less daylight and more time indoors can reduce opportunities for release and expression. Stressors that might otherwise move through the system become compressed.

Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk has written extensively about how the body holds emotional experience when it is not fully processed, noting that tension patterns often reflect unexpressed or unresolved stress rather than physical strain alone.

This does not mean tension is psychological in origin. It means the body does not separate emotional and physical experience. Both are stored in the same tissues.

Why Tension Often Surfaces at the End of Winter

As winter begins to lift, the body starts preparing for movement and expansion again. Increased daylight, rising temperatures, and shifting routines send signals that it may be safe to mobilize.

Ironically, this is often when tension becomes more noticeable.

The nervous system begins to thaw before the tissue is ready to follow. Muscles that have been holding quietly now resist movement. Stiffness becomes apparent. Fatigue surfaces.

This is not a failure of the body. It is communication.

What the Body Needs Instead of Force

When tension has accumulated slowly, it does not respond well to sudden intensity. Aggressive stretching, abrupt increases in activity, or pressure to “get moving again” can trigger more guarding.

The National Institutes of Health emphasize that gradual, supportive interventions are more effective for restoring mobility and reducing chronic tension than abrupt changes. The body needs time to feel safe enough to release.

Gentle movement, warmth, touch, and consistent regulation signal safety. Safety allows letting go.

Conclusion

Tension that accumulates over winter does not arrive with drama. It settles quietly, shaped by reduced movement, cold temperatures, nervous system adaptation, and emotional compression. Because it builds gradually, it often goes unnoticed until the body begins to ask for care.

Recognizing this pattern allows for a different response. One rooted not in urgency or correction, but in patience and support.

As winter comes to an end, the body does not need to be pushed forward. It needs to be met where it is. When tension has been held quietly for months, release begins with listening.